Water, Tree, Heart: Mapping the Driftless Area

Catherine Young

published in the 2013 anthology

Imagination & Place: Cartography

I love looking at maps. They are symbolic books of land and its history, for they express how we perceive place. At the same time, maps shape our sense of place.

My place is the Driftless Bioregion of Wisconsin. It is a real location, yet within Wisconsin it lives in an imaginary world defined by maps, just as Wisconsin, like all states, is an imaginary concept we apply to place.

If I were to take you on a cartographic journey of my home, the Driftless Area of Wisconsin, I would begin with the official state highway map. When you open it you will look for the enlarged image of what we Wisconsinites imagine as a very shaggy mitten with the thumb in the east poking into Lake Michigan and the ring finger in the North dipping into Lake Superior. The southern border of Wisconsin, like the edge where mitten meets wrist, is a straight line, an imagined boundary placed across former prairies and savanna, forever separating them from the prairies and savannas which covered Illinois. To the west Wisconsin ends in river shorelines; its borders defined by the paths of the St. Croix and Mississippi Rivers. Wisconsin is part of the Upper Midwest, a mostly glaciated, lake-dotted landscape. Within its borders is found more water than any other state, and within its borders you can find the Driftless Bioregion, where nearly all the waters run away from us to the Gulf.

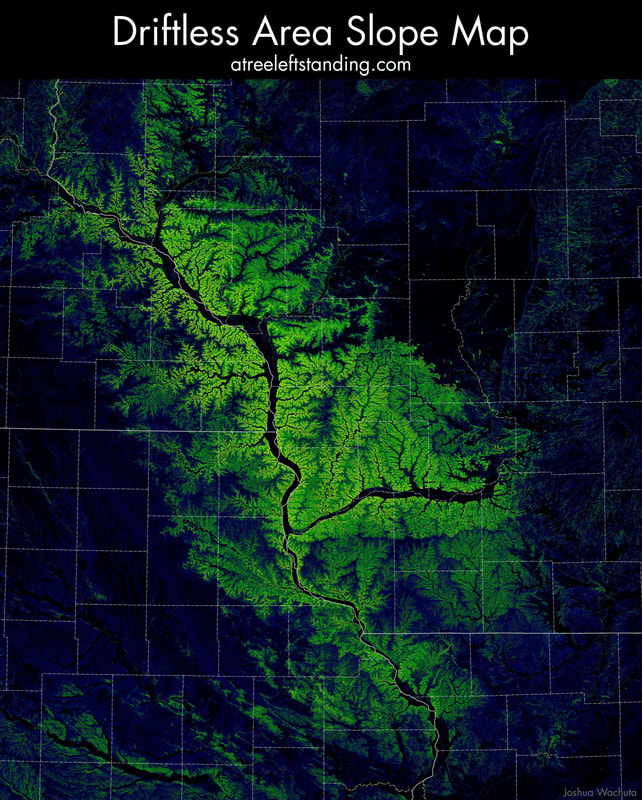

Imagine you are about to enter this new territory – my landscape of Wisconsin's Driftless Bioregion. When you look at the highway map you might be challenged to find the Driftless Area, for it is not labeled, though it is distinctive. The patterns of roads throughout most of the state are straight, bordering townships, or they curve around lakes. As your eyes drift to the southwest corner of the map, where Wisconsin borders Iowa and Minnesota, you’ll see there are no straight lines to represent roads – all the road lines squiggle. The Driftless Region’s appearance is unmistakable: roads in this area cannot easily move straight on through. It is a land of fluvial sculpting: a river-shaped place of ancient design. Here, glaciers did not scrape off hilltops; fill hollows. While waters were trying to decide which way to run over and through the glacial features of the rest of the state, the rivers here, predating the glacial onslaughts, continued to carve the hollows deeper and expose rocks within which can be found hidden crystals. The roads in the Driftless Area curve, bend, and sway along streams and through hollows. They follow the snaky paths of ridges. Only a few small township roads here and there are right-angled, built to protect the integrity of a human-designed field.

Maps are documents of relationship. Cartographers define those relationships and our perceptions of them. Often they take the birds-eye view. My view is from below.

I am lying on my back on the north wooded slope on my land. From my view I'm at the center of the world; all the trees lean over me and circle. If I were to map my place here, I would be making a trail for you to follow and find me.

Before the 911 system came to our county two decades ago, our addresses consisted of postal box numbers along numbered rural routes. Before GPS was used, the parcel delivery truck driver for UPS could not find us. Our address indicates a small town across the broad Wisconsin River in another county ten miles from our actual location.

The driver would go to our post office and ask for directions. Linda, our postmaster, would respectfully call Christie at the telephone cooperative across the street, and ask her to call us on our unlisted phone number. Christie would call us and tell us that Linda was trying to reach us. We would call the post office and Linda would ask if she had permission to give directions to the UPS driver from the post office to our place. Linda did this time and again, for she shared our landscape -- our need for privacy in our rural place. This is a map of respect and connection to one another to uphold the dignity of a farming community. We choose not to be accessible to cartographers or door-to-door salespeople. We have not been available to be read as if symbols could express the difficulty of survival here, the tragic losses.

With GPS now so available that anyone with a fancy cell phone can view maps and aerial photographs, our farm is, in some sense, is easily located. But none of the computer generated maps can tell why our neighborhood has such strange divisions of phone number exchanges, mail routes, and rural weekly newspapers. All of this has to do with water. If you were to look at a hydrogeological map of my area you'd see the divisions of local watersheds depicted with squiggly blue or orange lines. The lines delineate the ridges where water must choose to flow one way or the other to tributaries. Unless you dwell here and know where each creek flows, the drainage divides are imperceptible. Yet phone numbers, mail, news, and school districts divide along these boundaries. It all has to do with water.

When I tell stories about my Driftless Bioregion, I most often turn to a map of water. To understand this place, you need to follow water trails, and go to the sources of spring-fed creeks, where waters bubble up through fine beige sands. The spring waters push up through the sands like boiling porridge, but are cold and clear. They push out of their pools and begin to run, carving away this river-shaped land, creating hollows among the limestone hills, carving bluffs from sandstone.

My training was in fluvial geomorphology: the geography of river-shaped landscapes. I once held a job as a stream surveyor and sedimentologist in southwest Wisconsin. I felt a wild thrill when taking a county highway west out from our state capital and crossing into the Driftless Area. We'd ride over the sandy glacial outwash plain, covered by fields, and then suddenly tip off the edge into an area of hummocked hills. As we continued traveling west, the contrasts between valley floor and hilltops grew more pronounced. All at once we could see the bedrock outcroppings: the layered bones of our land. My whole body would relax at the sight of hills, the scattered trees, and the running streams heading south and west to larger rivers.

The purpose of our work was to learn the history of human impact on sedimentation of all the streams feeding the Kickapoo and Galena Rivers. By sending a probe down into the soil and retrieving a core, we could record the flood history of a whole river system from the time of settlement in the 1830's to the present. We were searching for the buried presettlement soil surface – distinctive as a dark, almost black band beneath coffee-with-cream-colored deposits. Amid rows of growing corn plants we would plunge the narrow metal probe to pull out soil cores an inch in diameter until we hit the original surface. Sometimes we would hit it at 3 feet down. At other times it was 15 feet below where we stood. We would marvel at how deep it was. Because of unregulated farming practices, massive amounts of soil were eroded and deposited farther downstream, hence a buried landscape beneath our feet. The Galena River, which had floated steamboats in the first half of the 1800's, had filled in and narrowed to the point that steamboats later could no longer ply up river, for the river was barely wide enough to handle a rowboat. Occasionally on streambanks we could see the buried prairie soil, a soil developed under the care of indigenous people over many, many centuries of living here.

The work gave me an intimate picture of the Driftless landscape. I knew it by layers of flood deposits, by crops grown over each summer through which I waded with my survey rod. I knew the sunlight, rain, and ever continuous flow of streams heading to the Mississippi River. I spent the days on dairy farms, talking with farmers about their work as we asked their permission to cross among their Holsteins on thistle-covered pastures. While we probed and measured soil, I stood in a strip of cornfield along a tributary. Meadowlarks filled me with song. Like a plant I stored sunlight for the darker times: working indoors in a laboratory, fall through winter. Sometimes I plunged into streams and simply stood, becoming a part of the living trail of water. I felt its gentle push, and I wished I could float away. In those years, the lands of the Driftless Bioregion called to my heart, and I wanted to answer, calling it home.

When I hear the word, driftless, my poetic ear hears shiftless (inefficient) and shifty(deceitful or resourceful; changing positions) and I shudder. Our area is named Driftless not for its lack of stability, but for its lack of glacial ice deposits. Glaciers did not ride our rugged Driftless landscape. This is a land of erosion, wearing down over time, steadily. It is a unique land region in the Upper Midwest: the place geologists say the glaciers missed time and time again over 200,000 years. It is an ancient river-carved land, the remnants of North American landscape as it may have looked before glaciers swept from the North and retreated over and over. Though the region is part of four states: Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, it is Wisconsin that holds the largest part of the Driftless Area within its borders. If you look at a map of the Driftless Bioregion you'll find that in Wisconsin it encompasses 14 counties. Names of these counties tell of the French fur trade, (Trempeleau, Vernon, La Crosse, Lafayette, Juneau), indigenous people, (Sauk, Iowa) settlement, (Grant, Crawford, Monroe, Jackson, Adams) and hopes for agriculture (Richland.) Where the Driftless Area is bordered by the Mississippi River on the west, the land is most strikingly carved into steep bluffs.

My county is Richland, and I love its name: rich land, which is so very true of this place. I live in the center of the region, where the hills rise round-edged above steep, narrow valleys we call coulees and hollows – using the words interchangeably as we please. Hills are simply called hills except for the region in the center where I live, where the hills stand out above wide river valleys. Here the hills are grandly called the Ocooch Mountains. Unlike mountains, such as the Appalachian, or the Rockies, which sweep back up and away from the valley floor, our hills, our river bluffs, are like little islands we can traverse up and down and across.

The Driftless Bioregion is a place of edges – a place with a view, and an area rich in biodiversity. You'll find islands of native prairies on bluffs; mossy sandstone streambanks bearing remnant hemlocks and pines from glacial times, and hills richly forested in contrasting species. Here northern flora find their southernmost edge crossing over with the northernmost reach of southern species. Where we see hills, we see diversity from bottom to ridge, from sunlit slopes to shady glens. On a south facing hill you'll find forests of red, black, and white oaks, shagbark and pignut hickory. On an opposing hillside you find sugar maple and basswood forest. Sunlight and shadow so affect the microclimates within our hollows that you can find plant communities which are typical of faraway northern Minnesota's boreal lands. Within the crevices of our hills golden birch trees hide, and wintergreen creeps along the ground. At the bottom of one north facing slope along our road where snow is late to leave in the spring, the wild strawberries grow luscious and most sweet, and above them grows small forest of white birch trees.

Coulee lands display a diversity of colors: a living map of our area in the growing season. You could map the trees here by the hues of their unfolding leaves in spring, or their revealed leaf colors in fall. The contours of the farm ridges could be mapped in summer by the stripes of corn, and oats – stripes that alternate in June between grass-green young corn and blue-green oats, to the palette of July: shiny deep-green cornstalks against rose-amber ripened oats. Below the ridges, the shadowy shamrock color of summer woods hides the ever-flowing creeks.

Water has made us what we are in the Driftless Bioregion. Ancient seas laid clay, sand, and shells to create shales, sandstones, and limestones, and waters have continued to shape this land. If we were to map the forests, pastures, and creeks, or if we were to look at USGS contour quadrangles of our area, the patterns would tell the same story: each hollow in coulee country is a branch of a giant water tree. The pattern of the most efficient transport of fluid is dendritic. From spring to tributary to stream to river-- from capillary to artery – from fine roots to trunk -- from twigs to branch to trunk -- the patterns are all dendritic. It all begins with water. If we look at the entire landscape of the Driftless Bioregion, including all animals, our story begins with the water running through the branching veins in our bodies, and the water is running in branching creeks on our land to create the great long and slender branching tree called the Mississippi River basin.

As the waters run, they carve our land to reveal horizontal layers of sedimentary rocks, straight and striped in bands of ivory, golden ochre and rust. The creeks run cold and strong through the woods and fields, and chatter as they tumble through riffles. The waters float dreamily through pools, their currents listing one side to the other while they flash sunlight and moonlight in a speckled pattern. The spotted patches of light and dark hide the stippled trout that dash side to side, from open waters to pools of shade.

On our farm, the spring below our house is our source of life. Until we came here in the 1980's, the stories were carried that our spring was the gathering place for the sugar camps of presettlement people, Indian people who had always been here. When I asked my neighbors how they knew this, they shrugged. Their ancestors mostly came here from Norway, and somewhere in their bones, they have carried the sugar camp story from their pioneer ancestors to me. It is a map of memory; it is a map of continuity. When our family drills into the black maples on the north hill above our orchard and then pushes the spiles into the living trees in February and March, we are harvesting trees that were sprouted from the trees which were used by American Indians in their sugar camp. Each of us in our family take shifts through the night to sit down at the banks of the spring creek, where others have sat before us. We feed a wood fire, and boil sap: this is the first harvest and blooming on our land. It is a map of maple sap and syrup, of spring-fed trees and the harvest of sweetwaters.

Below our house, two creeks run. The small spring-fed creek feeds into the larger trout stream. Though our location is still east of the Mississippi River and has enough rain and snowfall to support forests, cottonwood trees line our creeks, just as they would farther west where they are the only trees growing. Quick growing and very tall, the cottonwoods tower over all the other trees. Their leaves sparkle above the water in the growing season. When all is lush and filled in with vegetation, their leaves are in constant motion, moving flashes of light, just as the streams below them flash sunlight when waters tumble over stones. I imagine seeing the cottonwoods from above: they are a map for the winged ones, saying: Here. Here is water and sustenance. Come here. Follow this trail.

I think of the water tree patterns in the Driftless Bioregion and of all of the peoples who have lived along their branches since the last of the glaciers receded from this region 10,000 years ago –waters that have made it possible for them to flourish, to follow, travel, hunt, and plant through time from native people all the way to the French fur traders two centuries ago who left their marks in names on maps: Wauzeka, Viroqua, Ontario, Muscoda, Sinsinawa; Prairie Du Chien, DeSoto, Belmont, LaFarge. Map names reflect our mining heritage: New Diggings, Lead Mine, Mineral Point. Names tell where indigenous people were pushed westward out from the Driftless Area: Victory, Retreat. And we get a sense of how settlers perceived this rugged unglaciated landscape: Hillsboro, Ridgeville, Clifton, Towerville, Rolling Ground, Rockton, Dell, Valley, Rockbridge.

After the settlement of European peoples, the place called Wisconsin became known for dairy agriculture, Wisconsin’s Driftless Area historically has been the most difficult to farm. Steep hills and narrow valleys made it challenging for early farmers and horses to create and manage fields and crops. Yet for about the first 70 years farming was successful. Cows continued doing what they always do: graze the areas unsuitable or too steep for planting crops. But after horse farming was pushed aside by tractors, the dairy agriculture in our area began its slow decay. Early tractors could not handle the steep ridge roads between bottomland and upper fields above hollows; farmers could not plant fence row to fence row to increase production.

Economically the Driftless Bioregion was the first area of our dairy state to fail. Even when all was going well in dairy farming, the area had the lowest per capita income – rivaling income of folks on the reservations before casinos were built. Many people left our area, and the ones who needed to be here stayed, desperately holding onto land. For the longest time the Driftless Bioregion was a backwater. Forgotten.

Then a few decades ago Amish and back-to-the-landers arrived, along with vacationers, artisans, organic farmers, and niche food marketers. More recently the Locavore movement has brought us Community Supported Agriculture farms.

When I first taught country school, my third-and-fourth-grade students told me about a mastodon found near Boaz, the tiny town in our neighborhood with a population of 119. I brushed it off as a tale to tell a new teacher, but indeed it was true: the mastodon bones found on Mill Creek are famous. My students also told me about a man named Harry, who lived in a hole in the ground, and that he had also lived in a combine through the renowned Wisconsin winters. I can map the spot where I met Harry, a speechless man with shiny pitch-black hands: hands that must have been permanently stained with crude oil, and I can map the place in the woods where Harry lived – just as was said, in a hole in the ground.

On a highway map you can find my local community. Five Points is truly a crossroads: five very small roads cross to make a lopsided star. The town used to boast several houses, a post office housed in a small farm store, a Norwegian Lutheran church, and a cheese factory. The church hosted families on weekends and during major life transitions; the tiny cheese factory was the community gathering place on weekdays. Stories of people, health, crops, weather, and politics were traded here.

But patterns of movement and our values changed over time. The town of Five Points disappeared. With the loss of the store, post office, cheese factory, and the farms, all the physical evidence that's left of the rural community of Five Points is the brick Lutheran church – and a road sign. When you travel to Five Points, where County Highway F crosses gravel town roads, you'll see a green sign with its name in white letters – but it's the word underneath the name, Unincorporated, that tells that the town is only a memory which we cling to, to define who we are; where we call home with each other. Now when we visit a local nursing home, I tell the residents: I live at Five Points, and if I get a smile I tell them which road I live on and whose farm it used to be.

Can we ever be easily located? Here at this moment, can we be found in this time and place?

You could find my road on a map, and perhaps a satellite map would tell you just how many minutes it takes to travel from one end of it to the other. But the road is gravel, and at certain times of year, is impassible. Satellite maps can't tell you that. Locally we know how to watch the fall freezes, the winter sky, and the spring melt to find alternate routes -- or stay home. In deep winter, generous layers of salt and sand are added on top of snows to make our road wonderful to drive, but it becomes a carnival ride in spring as the road melts and the gravel disappears below the layers of sand. Each summer more gravel is laid, and the road becomes unnecessarily rugged; we grip the steering wheel hard and drive slow. We take walks cautiously. Living here we each have a map of experience, day after day, season by season.

Our road is built of limestone. We ride over the backs of ancient sea creatures and quartz crystals which have filled gaps in the rock over countless millennia. The gravel on our road is golden which, when it shines against the melting snows of a cloudless March day, beautifully contrasts the blue sky and purple blue shadows on white, globular banks of "corn snow." The road follows the creek from mouth to its narrow source on the hillside; then climbs straight up to the county road on the ridge. I wonder what kind of people made this steep and crazy road, and how it was cut from the hillside. No one is now alive who can tell me how it was done, but I once found a book containing my township’s business notes from a century earlier. Within a cloth-covered record book, I read signatures of men who agreed to build the road—their florid handwriting covered a large page. I think about them and how hard they worked to put their place on the map.

Sometimes when I walk my gravel road someone in a car will pull up alongside me and stop. The driver and companion greet me, and maps in hand, will ask me if I know of any farms for sale in my neighborhood. The people are from faraway cities and the maps were given to them by local banks or realtors. I smile, shake my head, and continue my walk, which takes me past the empty houses of vacationers in my neighborhood.

Sometimes I leave the mapped road altogether and follow the wild trails of water, or of deer, whose trails are sensibly laid, crossing from ridge down to the best paths over the creeks. On maps you might miss that our hills are rich with coon and possum; deer and orchids; our springs are fragrant with mint. You might overlook the fact that the farms as seen in pretty pictures are mostly gone. In their place are crumbling barns and land gone back to wild woods. You might not see the family struggling to survive, driving the scraggly curving roads. Hidden beneath the bird’s eye view of the Driftless Bioregion are the people still holding onto land, as they farm and travel far to factory jobs. Hidden beneath the great view are all of us dreaming this landscape, a fluvial geomorphologic corner in the center of our country. In my imagination the Driftless Area is a holy place that holds field dreamers and risk takers: people tied to soil and waters in all the centuries since glaciers drained.

Sometimes I wonder if we could map our future here in the Driftless Bioregion by protecting the waters. I imagine building wind and solar energy generators, set-aside woods for watersheds, food, fuel, and work the rich soil to a grow diversity of crops.

I have never drawn a map or diagram of my homestead, this farm. I wouldn't want to know my place in abstraction. I have an internal map within me. I walk out the door and am surprised by snow crystals, or wild turkeys, or fruit on my quince bush. One night this last June, I heard geese passing overhead in the dark. Geese usually fly by day, and they fly through here in spring and fall. I wonder, which internal map were they using, and with which purpose? Every living thing on this land has a map of eternal memory.

Before maps and aerial photographs of everyone's land became widely available on the Internet, every few years or so we would see a small plane cross back and forth over our house making passes to take photographs. Within a few weeks a man would show up at our farm with a large full-color aerial view of our house, outbuildings, and crops. Mostly I would send the man away – I did not need that view of our land. Only one time I purchased his photo, for it broke my heart. It showed our gardens with our toddler in it, sitting among the corn stalks with the babysitter. It was truly a map of time’s passage: an image with which I was deeply connected.

Over time I have learned that the Driftless landscape is rich with songs of redwings, meadowlarks, and barn swallows in summer, and that the songs of creeks are louder in winter than any birds. Our area is redolent with the scents of moist limestone along shady waterways, new-mown hay, nose-tingling cold. Beyond the map of curvy roads is land of hollows and rounded hills whose stones are filled with flint and grainy crystals that sparkle garnet, pink, amber, white, maroon.

I have an eternal map of the Driftless Bioregion within me – it is intertwined with the visions of cartographers. The map tells me this:

We are branches of a tree; branches of a stream; arteries of the hearts of all who dwell here. The pulse of springs regulates our hearts' rhythms while we pulse with life in this place.

We live and work here, raise food and families, but are as ephemeral as fireflies. We are here for a while, then away, and the waters keep pulsing out and away while we become part of memory: we played here once; we were lifted by starlight and dawn; we picked up crystals and stacked them.

**************************************************************************

Trained in fluvial geomorphology, Catherine Young worked as a national park ranger, farmer, mother, and educator. Her ecopoetry and prose is published in journals nationally and internationally, and her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best American Essays. Rooted in farm life, Catherine lives with her family in Wisconsin. Her writings and podcasts are available at http://catherineyoungwriter.weebly.com

Proudly powered by Weebly