The Crystalline Bed of St. Peter

Catherine Young

Still Point Art Quarterly Spring 2021

Issue 41 My Deep Love of Place

Is it strange to say I am in love with the bedrock where I live?

I am smitten with the layers of limestone and sandstone that line these Wisconsin hills, and to my eyes, these hills are the loveliest of golden layer cakes. Here on our farm, I love the scent of the bedrock, rising above spring waters, creeks and rivers and how the golden gravel lining our roads catches winter’s light against the white, blues, and purples of snow.

It’s been over forty years since I first stepped onto the land in southwest Wisconsin, examining the beautiful layers of stone through a university geology class. This place captured my heart. I recognized that this land of golden soils fragrant with limestone and cheddar was where I belonged; this land would be my home. I focused all of my university studies on every aspect of the Driftless Area, this island of unglaciated land in the upper Midwest. I wanted to learn how to live here with its millions of years of fossilized sea creatures and its artesian springs roiling through fine sands. I wanted to know everything I could about the First Nations people and the colonial people who pushed them away and built Dairyland. I wanted to know how we could live here without doing harm, choosing renewable energy, raising our food organically, drawing attention to the importance of local foods, and celebrating our multitudinous waters.

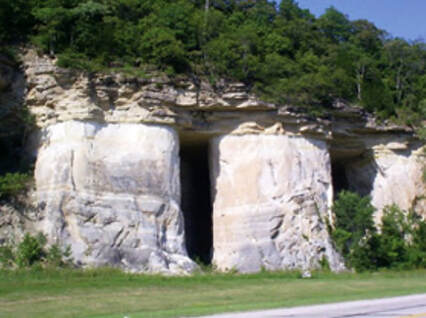

Of all the layers of bedrock here in my region, the St. Peter Sandstone draws me to it like a magnet. The Ordovician formation from 450 million years ago extends from Minnesota to Arkansas, including bluffs along the upper Mississippi River from the Twin Cities to northeast Iowa and southwest Wisconsin where I live. I love its colors: silver-white, cream, pale ocher, sometimes stained rusty red. Its cliffs along creeks and rivers glow verdigris from lichens encrusting its edges. Mosses completely cover boulder-sized pieces broken from the St. Peter, coating them in brilliant yellow green so plush that it’s hard to separate flora from stone. For me, this bedrock is alive. Separating stones from plants, microbes, or animal life would be like separating people from their stories. I cannot separate our family’s stories from the St. Peter. It forms the hills of our Mississippi River headwaters farm and holds between its rounded sand grains the spring waters essential to all life.

I plunge my hand into the frigid waters of our spring creek below our house. Year round, the creek releases its fragrance of submerged peppermint and spearmint, and I catch the scent of cold, clean, sand-washed freshwater. Following the creek to its source, I sweep my hands into the bubbling sands to feel the strong pulse of these artesian waters.

I have tried brief sojourns on east and west coast land of my country, even living once in Europe. I have lived and traveled in many places in and around my Great Lakes region. But somehow, whenever I stand beside a hill of St. Peter Sandstone, I feel happiest. I swear I can hear the crystals sing.

I think about the golden geology as I stir caramelizing whey on the stove. On this January day long after sunrise, my teenage daughter sleeps upstairs. I drink my coffee and stir. I stir and stir and stir the cooking whey, watching it thicken. In Scandinavia, gjeitost—caramelized sweet cheese—and messost—sweet cheese spread—are made from whey saved from the cheesemaking process. The whey is cooked down (perhaps in an iron cauldron) for days. Whey-cooked foods speak to me of no waste, of setting a pan on the back of the woodstove and stirring it into a further gift of harvest. Like the process of making apple butter or maple syrup, it is the harvest of slow-cooked brown sweetness to survive the winter. I think about the comfort of warmth and how the art of stirring is associated with old women (among which I am) and herbalists. Part of my work in this life is to tend the hearth. I’ve been a homemaker here at our family’s artisan cheesery for the past two-and-a-half decades, and for this I am grateful, especially because, I admit, I’ve always loved cheese.

When I was a child in an Appalachian coal mining valley fifteen hundred miles from where I now live, I stood in a relief line. My most favorite food, the most exquisite food we ever had access to was an ocher-orange cheddar cheese. It had no label other than “US Government” stamped on its golden brown box. The flavor of that cheese was transporting. I now know that the cheese came from the dairy farms here in Wisconsin’s Driftless Area, aged in limestone caves farther south along the Mississippi River. If people are made of what they eat, I realize I have always been made of the golden bedrock that I now dwell upon. The food that I loved long ago carried the flavor of the St. Peter Sandstone-filtered waters. The scent of the living creatures of the soil led me here to study, and I stayed.

On this January day in Wisconsin, snow crystals barely dust the ground. Not enough to cross-country ski upon. Though November brought cold, I cannot remember but one snow we had and that melted away. Only one snow coated our farm in December. Over a year of extreme rains and frequent floods in the past decade have raised the groundwater and changed everything. As farmers, we clearly see and try to survive the effects of climate change as well as the changes wrought by our larger American culture. Herbs and shrubs cover the ground, line the roadways, and fill the forests. The farmers who kept this land cleared with grazing animals are gone. Our township, comprised of contiguous dairy farms had, until last year, only one dairy farmer left—a man who milked and cared for the most beautiful Swiss cows. Our family no longer milks dairy goats, and our family’s farm is the last in our hollow to keep and work with farm animals. Our remaining goats browse, keeping only one small area over ninety-five acres open. Our work now is to hold on.

For thirty years I have watched the arcs of the sun and moon rise and fall above the hills in our hollow, lived within its shifts and crossings through the solar and lunar months and years of light and darkness. Within these arcs, I have birthed and raised my children. I’ve marked my time rising and working, seeding soil, weeding, fencing, hanging laundry. I’ve planted, harvested, and planned; stacked wood and fed the wood stove. I have nurtured generations of farm animals as they’ve grown and passed and fought against predators and their progeny.

Sometimes my love for this place is hard to put into words. Now my love for the St. Peter Sandstone is tested by loss.

The St. Peter Sandstone is comprised of almost pure quartz and for many years was mined for glassmaking and for use in foundries.

Now it is mined for frac sand in oil and gas drilling. The loose sand is pumped in a liquid mix under high-pressure into wells where sand grains wedge into and hold open any fractures in the rock, allowing the extraction of crude oil. Sand mines appear in our area without any warning. This extraction misses the most essential feature of our geology. The real gift for all of us is that the St. Peter Sandstone is perhaps the greatest freshwater resource in our country. It is lifegiver.

I keep thinking about how to best care for this place. Once pulled apart, the layers of rock put down by ancient seas over millions of years ago can never be put back together. For me the rock is completely alive. I think about the famous environmentalist Aldo Leopold’s land ethic: a thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community and is wrong when it tends otherwise.

I tend here. My roots are hidden between each grain of the St. Peter Sandstone, and when you see me, you may not know I am composed of mycelia; my heart beats with the pounding of the trout stream waters. My life is comprised of people, animals, and waters that have carried the crystals of St. Peter through every waking moment.

Proudly powered by Weebly